An institution primarily in service of the physically disabled, Jesse Spalding School, located at 1628 W Washington Boulevard in West Loop, opened in 1908. Spalding, a wealthy lumber salesman, was an influential player in Chicago business and politics, as well as a significant donor to Spalding school’s spiritual predecessor, the Home for Crippled and Destitute Children (Conklin). In its heyday, Spalding school served students from nursery through high school. The original Spalding school was built in 1907, with its elementary and high school buildings erected in 1928 and 1942, respectively. Additionally, Spalding School had twelve outside branches that offered bedside instruction, including Mercy Hospital, Cook County Hospital, and Shriner’s Children Hospital. From the first day of classes in 1908 to the final bell in 2004, Spalding stood at the forefront of disability education, setting the gold standard for accessible education in the city. Over the years, Spalding acted as a meeting point for the charitable and scientific communities of Chicago, both of which had fundamental roles to play in shaping the pedagogy and culture of the institution. For almost a century, the tensions between private and public played out in the hallways of Spalding, making it a dynamic site for change and debate.

In many ways, Spalding was a product of its environment. Despite claiming to be the first institution of its kind in Chicago (The Torch), the incorporation of Spalding school was in fact the result of many years of sequential efforts to expand the opportunities of disabled people. By the 1800s, there were virtually no public or private programs in the US to address the specific educational needs of handicapped students, nor was there adequate support for the health and wellbeing of these children beyond small-scale or individual charity. In fact, it was not uncommon for educational institutions to expel even disabled students who could keep up with coursework for no other reason than being viewed as "depressing" or "nauseating" by their instructors (Fleischer). However, as the percentage of individuals who were left with permanent disabilities began to rise during the tuberculosis and polio epidemics, there was a more concentrated attempt by the Progressives to address the issue of educational exclusion more systematically.

In the early 1900s and 10s, small, private philanthropic organizations were the only option for those most in need. In many ways, the small charitable operations like Home for Destitute Crippled Children sowed the seed that would soon bring to fruition a number of public programs and facilities for the use of disabled students. Dedicated in 1890, Maurice Porter Memorial Hospital was a small, private institution that provided free orthopedic medical care to children with disabilities. The home functioned primarily as a hospital, but also pushed for the educational and vocational development of its inmates. Though the hospital could only host a humble dozen or so children at a time, the mission of Maurice Porter’s soon grew. Eventually, the home was incorporated as “The Home for Crippled and Destitute Children.” In its bylaws, the Home was unique in that it mandated daily educational programming, as well as provided for transportation for students. From there, an Official Building and Aid society was established to find a bigger space for the institution, the meetings of which many prominent citizens and religious representatives attended. Under the leadership of the wife of the Board of Education's superintendent, the school was integrated into the Chicago public school system (Rankin). Though small, the Home put the interests and needs of the children it served first, and was in many ways seen as embodying the spirit of the Progressive era.

The Home for Crippled and Destitute Children set the scene for Spalding in two major ways. The first was the presentation of a report recommending that the acting superintendent be asked to “formulate a special type of education to be given to crippled children. " This recommendation, informed by the work of teacher-in-charge Emma Haskell, would lead to a survey and subsequent expansion into Emerson School. The second, more broadly, addressed the transportation issue plaguing disabled students and their caretakers. On the logistical difficulties of attending a special school, Chicago was the first to address this by funding a transportation program for handicappped students. The omnibus line, also spearheaded by Haskell, was officially authorized in 1901. The omnibus line provided a means of free transportation, completely maintained by the CPS as opposed to charitable institutions. Extra support was provided for children who needed to be carried from the bus to the door of their school and homes, as well as the stationing of police officers as drivers to ensure safety. Additionally these school buses were available to transport students to hospitals and doctor's visits, if need be (West Side Council of Parents and Teachers Records). This crucial service was provided under the threat that, without means for getting to school, these children would grow up in ignorance and become burdens for future taxpayers (Rankin).

Like its contemporaries, Spalding was an experiment in education. In an educational movement grown from increasing disability visibility and the development of hospital and special education programs, Spalding and its contemporaries were among the first in the country to bring accessibility to the forefront of educational pedagogy. With neighboring programs already overcrowded, the Commission on Building and Grounds specified that the construction be separate from previously established schools, making it the “main institution for [...] surgical and medical care” of students with disabilities (Rankin).

Spalding's initial population was quite small. In 1938, the Spalding graduating class was composed of 20 youths, 19 boys and one girl. At this point in time, Spalding did not yet have a high school division of its own. Then, in 1941, a $750,000 addition doubled Spalding, and in 1942, Chicago Public School system voted to transfer the Lindblom and Tulely high school special education branches with Spalding. By the 60s, Spalding was serving children from the West and North sides in its elementary school, as well as students from all over the city in its high school, with a student body topping out at over 1,200 (“Kids Will Benefit from Bazaar”).

Despite the leadership drama that would go on to plague Spalding (and the wider CPS system at large) in sequential years with the ousting of Emma Haskell, these so-called “smear campaigns” were not uncommon events at Spalding. In 1942, the president of the board of education, James B. McCahey, responded to criticism that arose with the removal and replacement of Principle Olive Bruner with Celestine Igoe. Unlike early Spalding leadership, Igoe had an advanced track record, including holding a masters of education and working as a teacher and principal at the high school and elementary levels for 25 years (“M’Cahey Tells Why Miss Igoe Heads Spalding.”). Under Igoe’s leadership, Spalding would continue to grow, expanding its program offerings and adding a nursery program for children with cerebral palsy. Throughout the later half of the 1900’s, legislation regarding the education of disabled students became more inclusive and unified in its execution. Programs that were once thought of as experimental at Spalding became the industry norm.

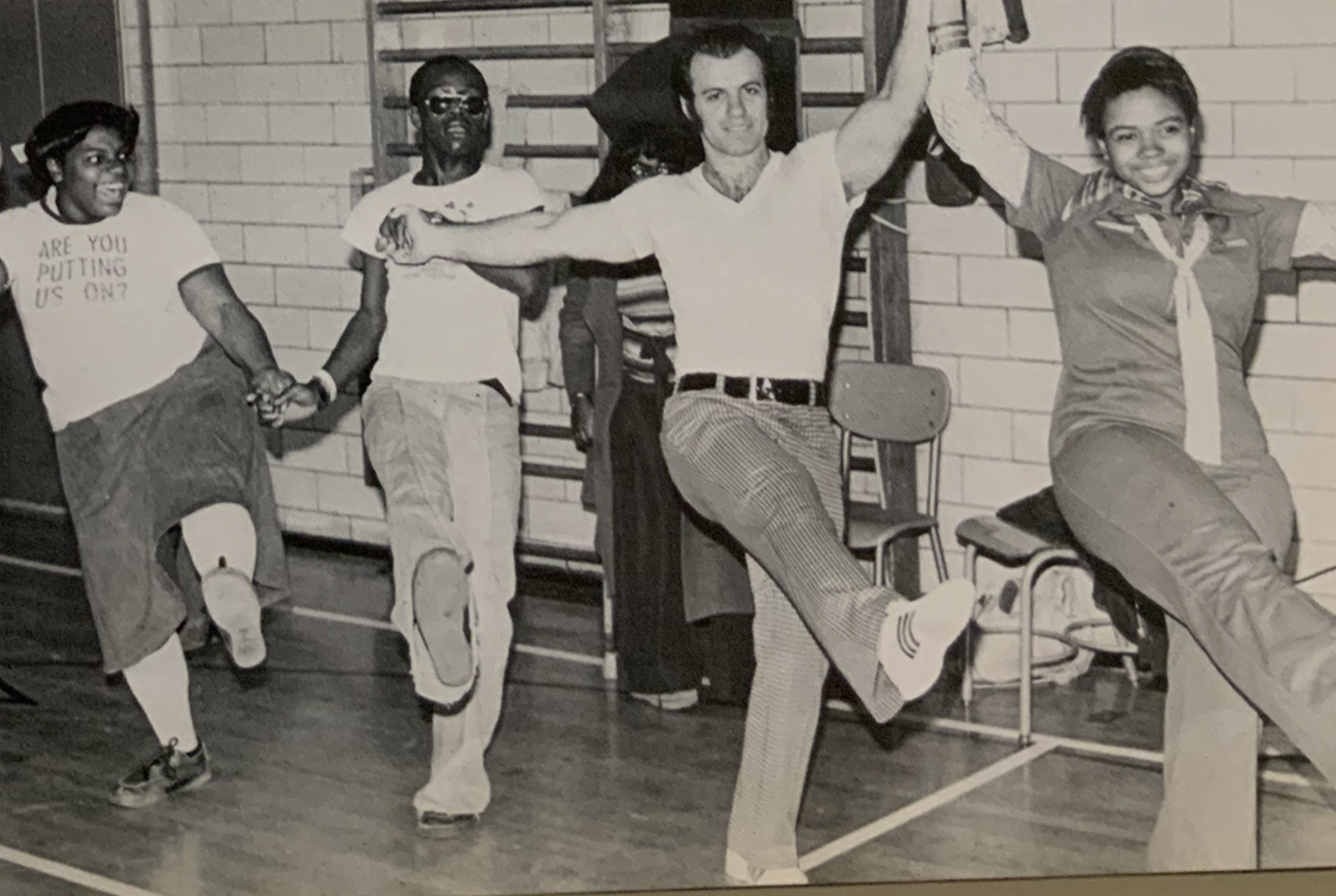

From “cardiacs” to “spastics,” students at Spalding truely spanned the gamut of visible and invisible disability. Unlike schools for the deaf or blind, students at Spalding regularly interacted and socialized with students with disabilities far more or less severe than their own. Some articles have reported that around 25% of students at the school use wheelchairs (“Spalding School helps handicapped find place in society”). This medical mixture called for a diverse repertoire of treatment programs. Though total staff size ebbed and flowed over the years, at the height of enrollment at the institution, teaching staff only constituted half of the employees. The other half (excluding bus drivers and facilities) included physiotherapists, classroom attendants, and general and specialized nurses. Physiotherapists were required to be certified by the Board of Education. The purpose of these specialized nurses was to operate the ultraviolet treatment room and supervise surgical dressings and emergencies. Spalding provided specialized care in sectors that had been historically lacking, such as centers for the treatment of those with cerebral palsy, which the Illinois Association for the Crippled had been advocating for years (Quarterly Bulletin of the Illinois Association for the Crippled, 1942).

The nursery at Spalding was also quite cutting edge for the time. In 1942, a group of parents helped organize the program specifically for babies with cerebral palsy. This program became the first of its kind in Chicago, as prior there were no provisions for the public education of children under 5. In its early days, the nursery accommodated 16 children between the ages of 2 and 4, and was staffed by a teacher and two physiotherapists. Like Spalding elementary, Spalding nursery was designed to accommodate both the academic and practical needs of its students, including both basic features like a room for rest and special features like equipment for therapeutic exercise. Though the program was public, parent organizations shouldered some of the fees of staffing the physiotherapists, though this amount was adjusted or waived if the parents were unable to pay (West Side Council).

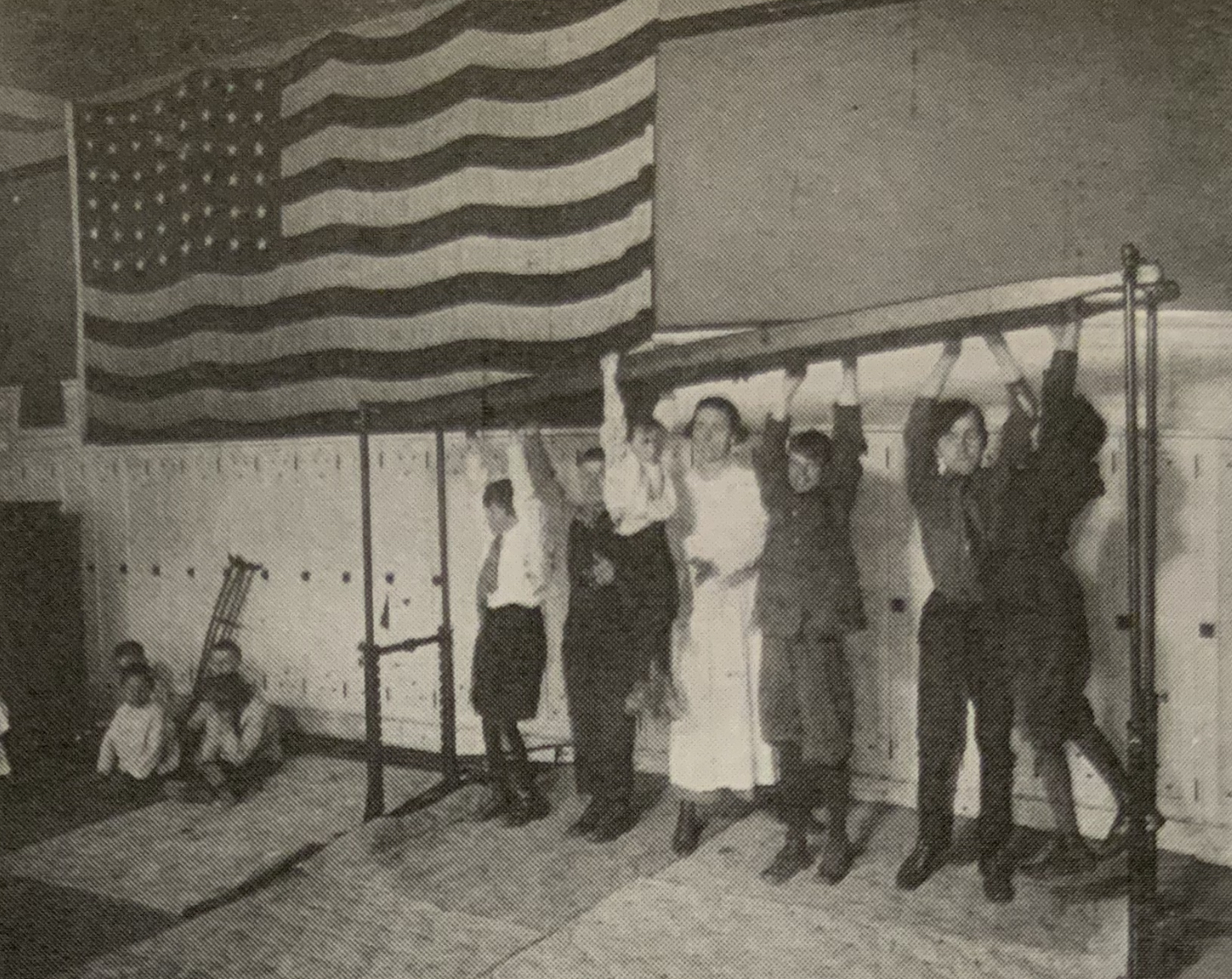

In a 1945 report from the Journal of School Health, Spalding was reported to host a variety of vocational and homemaking training resources in line with what was the norm at other schools at the time. Spalding elementary, in lieu of a robust physical education program, boasted a wood shop, cooking room, weaving room, clay modeling studio, and shoe repair shop. On the high school side, the list of spaces also included an industrial arts shop, print shop, wood and metal shop, repair shop, and arts and crafts laboratory. Spalding also emphasized the direction of extra resources towards its library, swimming pool, and social room, of which served mixed recreational and therapeutic purposes (West Side Council).

Additionally, the curriculum of Spalding was set up in a way that had treatment time built into the structure of student’s day, instead of at odds with it. Two important examples of this involve a dedicated hour for rest and a flexible lunchroom menu, in which students on special diets or supplements could request food. Still, there were aspects in which the school did not meet the non-educational needs of students. One of the earliest manifestations of this tension was in the formation of the “Willing Helpers for Crippled Children,” a group composed mostly of mothers at the school who sought to draw attention to and address the non-educational needs of students. The needs of these students ranged from mobility aids like braces and wheelchairs to everyday items like glasses and clothing. These women helped establish an in-school brace shop, as well as a standing eyeglass fund to cover the needs of students not met by the board of education (Quarterly Bulletin of the Illinois Association for the Crippled, 1941).

Though Spalding provided exceptional accommodations, some students were unable to remain in the physical classroom on account of worsening health conditions. In order to make sure that students stayed on track with their studies, Progressive educators experimented with new modes of teaching. The Board of Education arranged for special schools to provide hospital instruction. Though programs like these were already common in the 20’s, the polio epidemic in the late 40’s accelerated the formalization of hospital and homebound education. Educators from these institutions provided bedside classes for students who would have otherwise had no access to the classroom in their admission. After discharge, students continued their education from where they left off on entering the hospital. Students who were bedside learners for more than 5 months would often not be integrated back into their old schools post-discharge, but would be rather enrolled at institutions like Spalding which could accommodate their special needs (Rankin).

Upon graduation, students at Spalding high school had access to specialized career counseling resources provided by the Illinois Association for the Crippled. These adjustment counselors worked with students to find full-time and part-time employment opportunities appropriate to their skill-level and interests. Interviews were also conducted to educate and assess students on the physical expectations of their desired positions, as well as to inform them on beginning wages. Some Spalding graduates went on to become Physiotherapists-Attendants at their old school, conducting clerical work for the department. From there, the counselor would work with school clinics to confirm the nature and extent of a student’s disability, as to make sure the individual was “capable of performing without jeopardizing his health” (West Side Council). From here on, counseling and placement would follow the same preparation as a non-disabled student. In this sense, the staff at Spalding attempted to give their students the training and skills required to have a competitive edge in their chosen industries, while still addressing the fact that students were not machines, and thus had limitations that would require additional support. In this way, the philosophy of Spalding rejected that early American pass/fail mentality, acknowledging that every student had a different standard to live up to.

While it is true that Spalding remained on the cutting edge of educational accommodation and rehabilitation, it is also apparent that the school was becoming less and less of a spectacle. In 1991, the first students without disabilities enrolled at Spalding, and in 2003, like many other historic Chicago educational institutions, the decision was made to close the school and reassign students for the 2003-2004 school year.

Though undeniably sad, the closing of Spalding has come to signify many things. The first was that disability accommodation has come such a far way in Chicago that even neighborhood schools can provide adequate services for students that require them. The second was that the particular era Spalding was created for has ended, and is slowly being replaced by something else. Today, the idea of building an entirely separate institution to serve disabled students is considered outdated and somewhat offensive. Instead, most people today believe that it is the right of disabled students to attend classes with their non-disabled peers, opening up and expanding access to the classroom instead of segregating it.

As for the students of Spalding, alumni have come to disagree on whether they left feeling empowered or sheltered, and there is a degree of nuance we must take in making a definitive assessment about the school’s emotional legacy. One former ‘79 alum described his experience as "[a] sort of segregation, [in that] people get the feeling you're not normal in other ways” (Conklin). Alternatively, some graduates of the pre-mainstream system remain critical of the modern special education system. As another alumni explains: "Two things have evolved over the years in special education, and one has been an effort not to showcase the handicapped -- sort of a sequestering, to be polite about it [...] But in doing this, the second thing is that all the positives that can take place from mainstreaming don't happen. Unconscious or not, the twain don't meet" (Conklin).

Though the academic and medical approaches of the ‘old ways’ were soon mostly replaced by the ‘new,’ Spalding was unique in that it developed a culture that combined influences of both. The way in which Spalding centered disability was very novel. The institution treated and accommodated for physical disability, but never attempted to minimize or ignore it. Instead, those teaching and attending the institution fostered a culture where one’s disability was integral to their identity, extending not just to mutual understanding in societal discrimination, but also in a celebration of their status as people with lives, interests, and dreams, shaped by their experiences, but independent of the romantic expectations.

There is no one definitive Spalding narrative, in the way that there is no one definitive Spalding student. As with any system, Spalding was composed of many moving parts, from the advocacy of civil rights groups to the bureaucracy of the Progressives to the actions and opinions of the students themselves. And though the legacy of Spalding is often overlooked, the ways in which it centered disability culture while exposing and celebrating its nuances and complexities is an integral part of Chicago history.