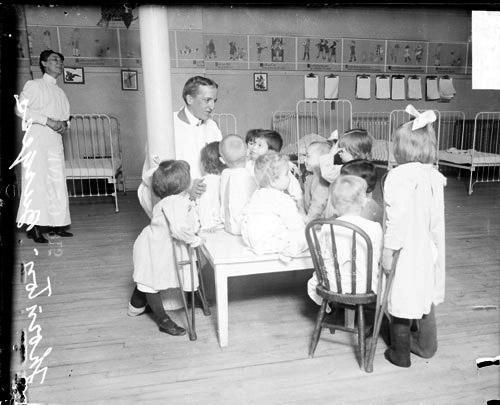

The early days of the special education movement were characterized by a distinct overlap in the provision of medical and educational services. While the two fields have always walked hand in hand in terms of institutional support, the blending is more distinctive here as the primary goals of institutions for the disabled were intended to treat, not educate. While the education of minors was an important tenet of many of these institution's philosophies, such as Maurice Porter Memorial Hospital, this education was moreseo intended to bolster moral fitness rather than provide an equitable education. The children served where patients first and students second.

Special education came to encompass a variety of forms. The first was the special school, which modeled the normative academic institution most closely while also providing additional support in the form of medical accommodation and accessible design. Next, was the convalescent home or camp, which while appropriate in terms of care, was more disruptive in the lives of children and their communities. These homes also were inconsistent in the quality of education offered. The last form discussed here was the hospital and homebound program, whereas instructors would come to the student for tutoring. This choice was perhaps the most inconsistent in the quality of education and socialization of the child. In examining these three strains of special education, there are a few key trends to keep track of: first the formalization of aid and services, next the influence of epidemics on educational policy and then the ongoing process of identifying underserved demographics.

In the decades leading up to and following the Progressive era, reformers and special interests groups pushed for the increase in quality and quantity of crucial services for the poor and marginalized. In order to address need in the short-term, philanthropic groups and figures attempted to fill the governmental gap. Though philanthropic efforts were an essential component in the development of a robust special education system, these groups could range widely in degree of effectiveness and long-term sustainability. Furthermore, the labor-force behind many of these privately-run programs was strictly voluntary. Eventually, many privately-run programs Though there were downsides to the bureaucratization of these passionate, creatively-malleable groups, the shift from voluntary to salaried work solidified access to special education as a right, not a gift.

Though the progressives and their interest groups did much to influence public attitudes, no interest group or philanthropic organization had as much power over policy as the epidemic. Sequential, debilitating epidemics characterized much of the early 20th century, each with its own patheon of preventive measures and long-term health complications. Progressive policy, thus, is so tied to epidemics as the pre-existing gaps in accessible education were exemplified under an influx of students with temporary to permanent health complications. As Scarlet Fever and Diphtheria tore through Chicago Public Schools, educators and policymakers also were tasked with finding quick solutions to rapidly-evolving situations, ultimately culminating in the creation of many experimental (if underfunded) programs and protocols. Open-air classrooms, convalescent camp teaching assignments, and homebound tutoring would all arise from this era, further solidifying the idea that any child could and thus should be educated, if only the public institutions themselves would put in the effort. Eventually, experimental programs became standard practice.

A shift from the overreliance on private charity to plug the care gap, the public institution in this era was slowly but surely changing the way it interacted with those it served. Following WWI, special education became an inseparable part of the Chicago Public Schools system. Under this system, more permanent iterations of Progressive programs were founded, with public bureaus working with and overseeing educators more closely. Still, even with the increase in consistency and quality of education standardization brought, special ed had a long way to go. In subsequent decades, those from within the Civil Rights movement would challenge inequity and segregation in public institutions, including disabled activists and students. Later, the larger push for disability rights would lead to more substantial educational legislation and mainstreaming. Still, special education continues to evolve as schools and students struggle to close the educational gap, not only in the US but globally.